Key Takeaways

- San Diego’s jobs recovery has left the lowest-paid workers behind.

- Disproportionate job losses and the possibility that lower-paid residents will owe large sums in back-rent will exponentially exacerbate wealth inequality.

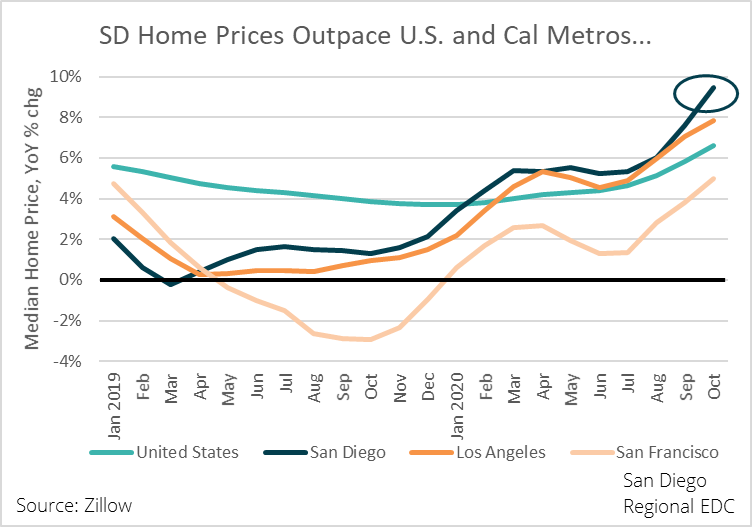

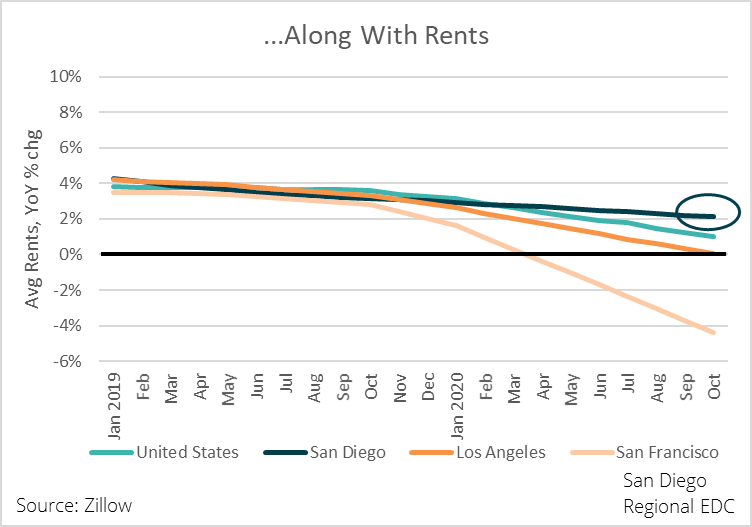

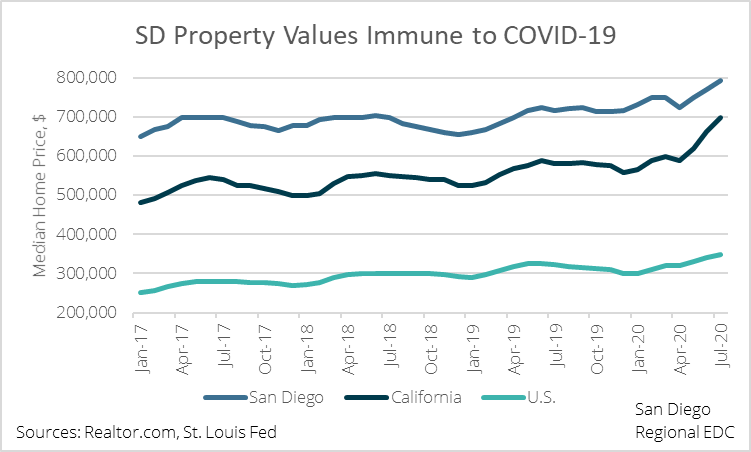

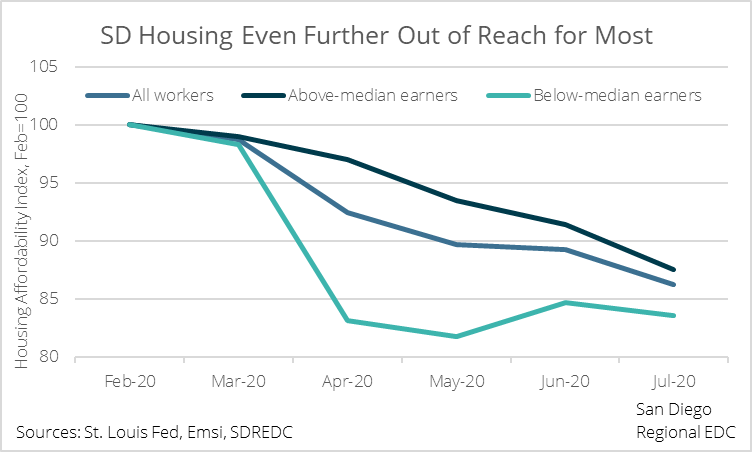

- Lower mortgage rates drove up house prices, making housing even less affordable despite record job losses and elevated unemployment.

Needless to say, 2020 was a rough year. But it was far worse for some than others.

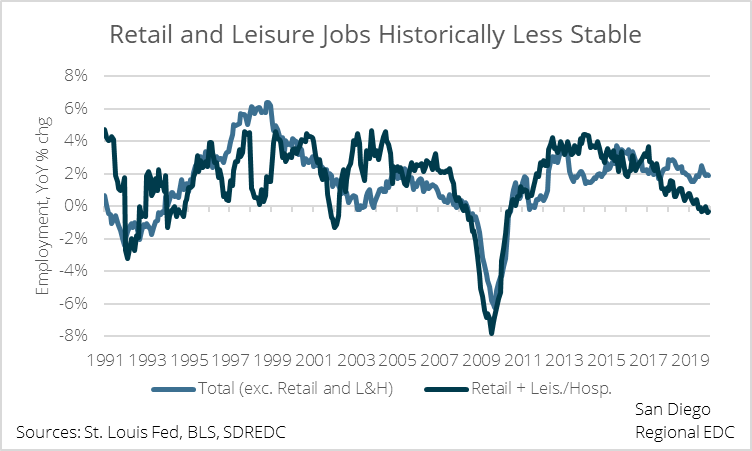

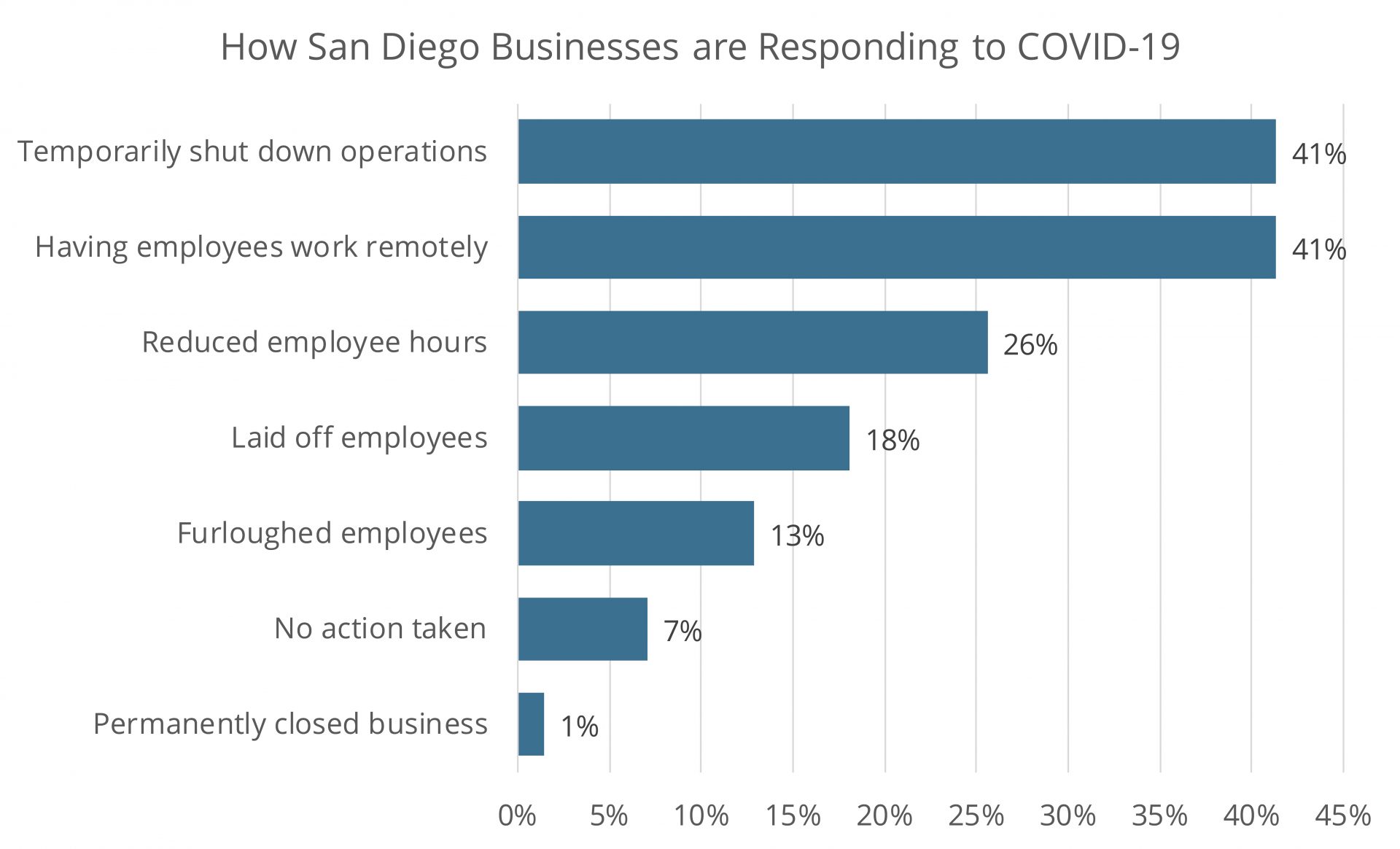

San Diego employers added a better than expected 14,300 jobs in November, including a generous push by retailers who put 1,800 people back to work even as retail sales backtracked. Nonetheless, the “K-shaped” recovery has persisted, where middle- and upper-income workers either never lost or quickly recovered their jobs while lower-income jobholders were furloughed indefinitely or laid off.

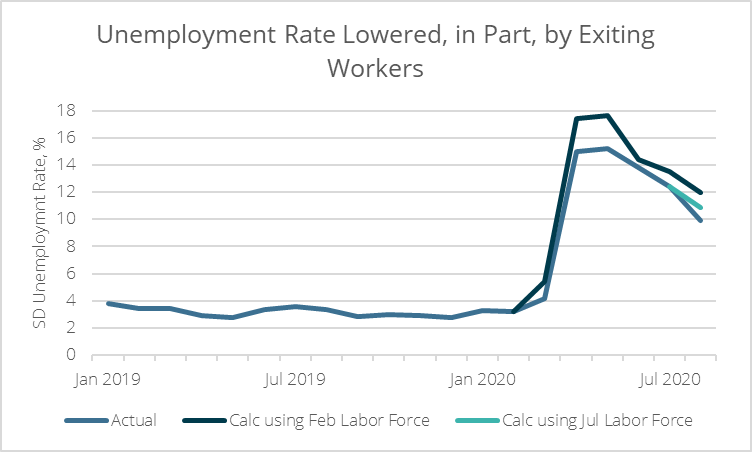

As of November, San Diego nonfarm employment rested 6 percent below its February 2020 peak. However, jobs paying less than $41,000 per year—the threshold associated with quality jobs in the region—remained stuck 18 percent below their pre-COVID peak. Moreover, low-income employment cratered by some 43 percent from February to April last year, compared with 15 percent for all jobs.

Additionally, six industries, including Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, have reclaimed all of the jobs lost to the COVID downturn, whereas wholesalers have recouped a meager 11 percent of the positions cut last year and information has only recovered one in eight positions.

This could have lasting impacts even after the jobs recovery is complete.

More than 60 percent of workers in the lowest-paid positions in San Diego are non-white versus 56.6 percent in all industries. So, to add “injury to insult,” minority workers that have suffered through months of intense social unrest this past year have simultaneously juggled disproportionate job losses.

Fortunately, eviction moratoriums were put into place last year that prevented many people from being evicted for nonpayment. But landlords can once again legally collect on back-rent or issue evictions if the statewide moratorium is lifted on January 31. People making less than $41,000 are far more likely to live paycheck-to-paycheck. In other words, a large swath of the population is entering 2021 with sizeable arrears to be paid off—something that’s tough enough for low-income workers even while employed, and even more difficult for the 18 percent of these folks who are still without jobs.

Worse, the wealth effects from this downturn have been particularly stark. Middle- and upper-income workers—most of whom already had some sort of savings and are much more likely to be homeowners—have been able to capitalize on lower interest rates and higher stock valuations all while holding onto their jobs. Meanwhile, most people making less than $41,000 a year were unable to amass significant savings, let alone any sort of real wealth, in the months and years leading up to 2020. The outright loss of income for so many of these workers most likely means an exponential widening in the wealth gap in San Diego.

HOMEOWNERSHIP EVEN LESS ATTAINABLE

Speaking of lower interest rates, San Diegans took full advantage of the 210-basis point drop in the 30-year fixed mortgage rate between November 2018 and November 2020.

San Diego’s housing market is significantly more sensitive to mortgage rates than many other parts of the state and country, in no small part because of the high cost of living in the region. In November 2018, when the average 30-year mortgage rate was 4.9 percent, the median home value was $659,500. A mortgage financed on that amount, minus a 20 percent down payment, would have totaled $1,008,118 over the life of the loan, or $2,800 per month. However, the cost of that same mortgage after the 30-year rate dropped to 2.8 percent would be $780,496, or $227,622 less than the 4.9 percent loan and $2,168 per month. Given all of this, rising home prices over the past two years or so make sense from a microeconomic point of view.

Even so, a 22 percent year-over-year increase in home prices as of December 2020 amid record job losses and elevated unemployment seems suspect. Indeed, calculating a housing affordability index that takes unemployment into account shows that housing has become increasingly unaffordable.

WE MUST TAKE ACTION

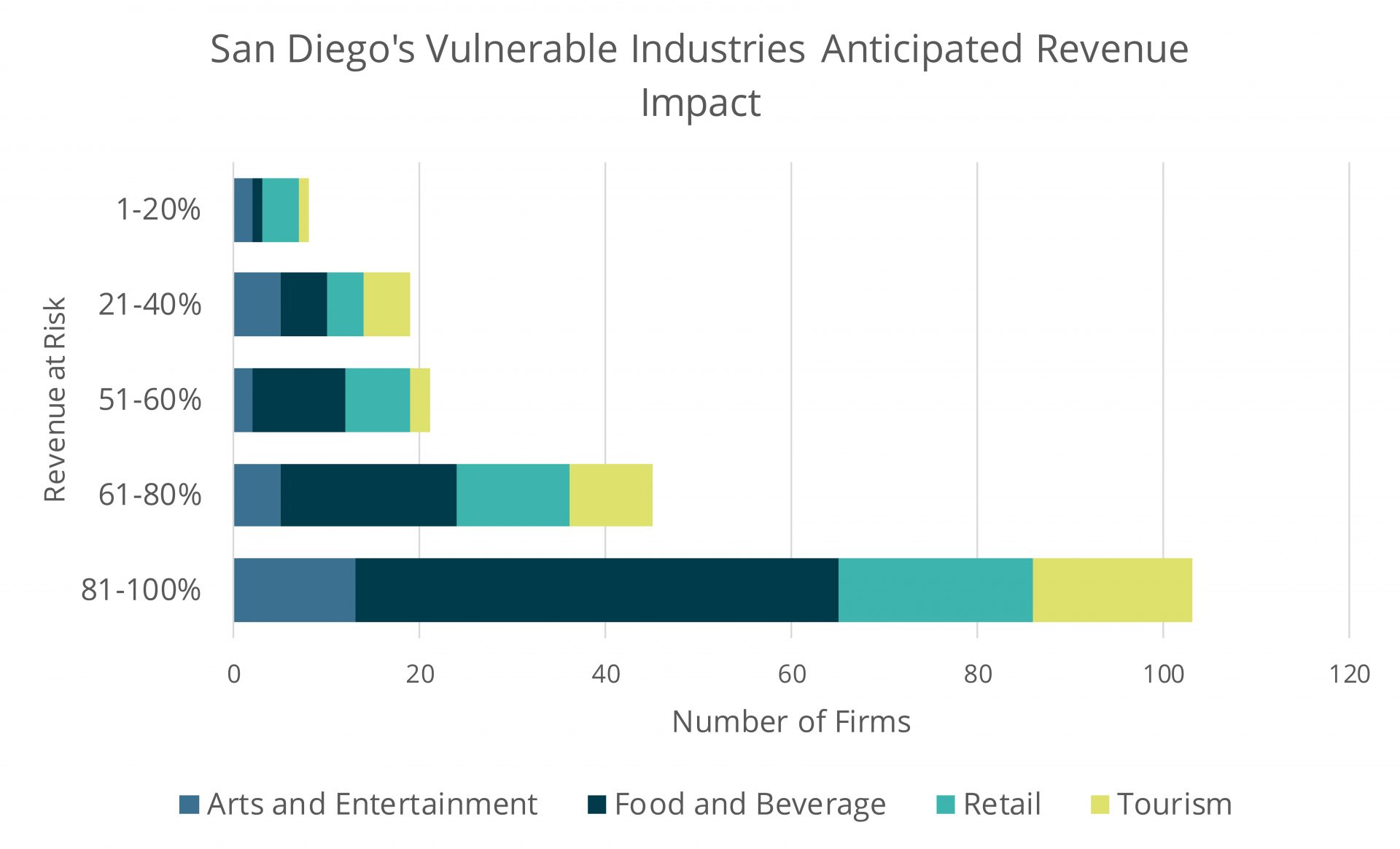

In sum, San Diego is likely to face myriad structural issues long after the economy has technically emerged from recession. Income and wealth gaps are likely to have been widened just like they have after each recession for the past 30 years. And jobless residents who were afforded a temporary reprieve from being evicted may find themselves in a situation where they owe large sums of money to their landlords.

A debt-ridden middle and upper-middle class has been tough enough on the economy as college graduates pay off their student loans. However, lower-income households tend to spend a much larger share of their paychecks than middle- and higher-income households, so having these funds siphoned off into repaying back-rent could disrupt consumer spending even more markedly for months, if not years, after the dust settles.

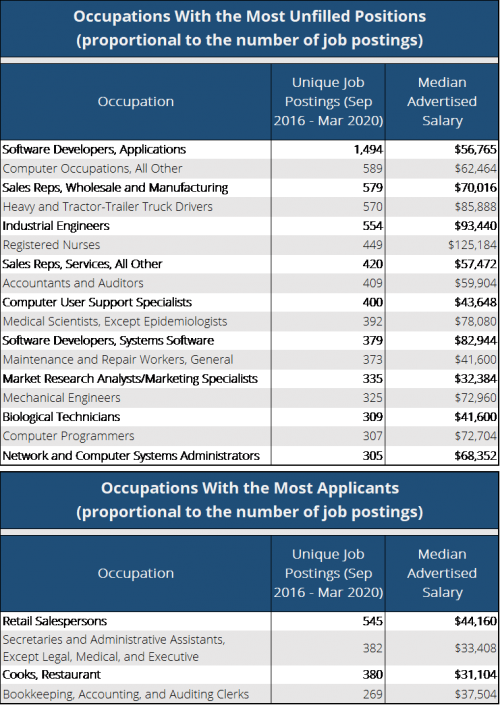

It will take more than just empathy to bridge these gaps and get this recovery right. It is now more important than ever to ensure greater access to higher education and worker training for our region’s lower-income households. Additionally, companies may also want to consider employee-ownership models, like Taylor Guitars, to give workers a larger stake in the economic fortunes of the businesses they work for. By offering a pathway to higher paying, more stable employment, we can ensure a more resilient and vibrant San Diego in the future, which will benefit all of us for decades to come.

Learn more about San Diego’s right recovery

You might also like to read:

7 COVID-19 resources for small businesses – January 2021

Economy in crisis: Job growth slows as we head into New Year

Economy in crisis: SD housing market advances, but geographic differences remain