Each month, the California Employment Development Department (EDD) releases employment data for the prior month. Presented by Meyers Nave, this edition of San Diego’s Data Bites (formerly the Economic Pulse) covers April 2021 and reflects the lingering effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the region’s labor market. Check out EDC’s Research Bureau for more data and stats about San Diego’s economy.

Key Takeaways

- San Diego establishments added 9,800 new payroll positions in April, with most industries adding jobs over the month, but March’s employment figure was revised lower by 2,500 positions.

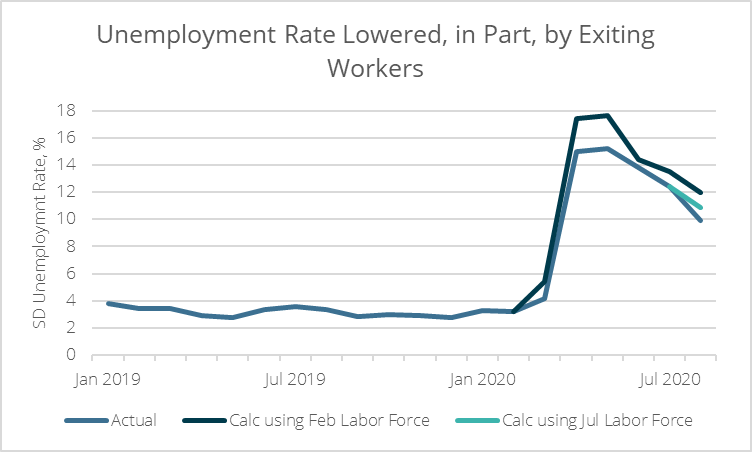

- The unemployment rate edged lower to 6.7 percent from March’s 6.8 percent. However, this was due primarily to the loss of 16,500 workers from the labor force.

- The flood of women workers exiting the labor force could reverse progress made on gender pay gaps and prolong the recovery.

First impression

The April employment report for the San Diego region was mixed. On the bright side, employers added 9,800 positions last month across a majority of industries, and the unemployment rate edged lower to 6.7 percent from March’s 6.8 percent. However, it was the loss of 16,500 workers from the labor force, not job gains, that lowered the unemployment rate. Moreover, March employment was revised lower by 2,500, reducing the initially reported gain of 9,900 payroll positions to 7,400.

Industry view

The battered Leisure and Hospitality sector led gains with 7,000 new positions, followed by 3,300 more jobs in Construction. Meanwhile, Healthcare and Social Assistance logged another 1,700 jobs, while Other Services—which include gyms and salons, among others—gained 1,600 positions over the month.

The loss of 3,500 Administrative and Support Services jobs weighed on growth in the Professional and Business Services cluster last month. Even so, Professional, Technical, and Scientific Services added 1,500 jobs and Management positions held steady. Elsewhere, San Diego’s Transportation sector lost 1,600 jobs.

The story for year-over-year growth has changed dramatically in the past two months. The jobs numbers for April 2021 show Total Nonfarm employment is 10.4 percent above April 2020 levels, when San Diego was in the throes of the pandemic. Payroll employment at clothing stores is up by more than 158 percent from a year prior while employment at restaurants is up an impressive 60.8 percent.

Fewer female workers could prolong (or even jeopardize) the recovery

Nationally, it has been widely reported that women have left the workforce in droves since the pandemic began. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the female labor force participation rate declined from 57.9 percent in February 2020 to just 54.4 percent in April 2020, representing the weakest participation for women since 1986. By comparison, the rate for men declined from 69.0 percent to 65.9 percent during that time period.

Labor force participation for women has recovered somewhat since bottoming in April 2020 but has vacillated at roughly 56 percent for the past year, well below the pre-pandemic peak of almost 58 percent. The BLS estimates that some 2.4 million women are yet to rejoin the labor force, representing five percent of all female workers.

California EDD does not provide separate labor force statistics for men and women. However, assuming a similar U.S. trend has played out in San Diego, there still may be as many as 35,000 to 40,000 women still missing from the regional pool of workers. This is compared to just over 30,000 male workers who are yet to come back.

There are two key reasons why female labor force participation has dominated the headlines in recent months. First, it may erode some of the progress made on the gender pay gap. Second, women workers have historically helped to replace men as they dropped out of the labor force; nationally, female labor force participation rose from just 30.7 percent in 1948 to 57.9 percent in February 2020 as male labor force participation declined from 88.7 percent to 69.0 percent during that time.

Unpacking these points, employers are inclined to pay workers less who have been on hiatus for an extended period than workers who never left the workforce. This is because it is widely assumed that some skills erosion may have occurred during that time. This could mean a smaller paycheck for a larger number of women workers than men once (or if) they return to the labor market in the coming months or years.

Since a larger swath of the female population has left the workforce than men, this could put measurable downward pressure on average pay for women workers, thereby reversing some of the progress made in closing the gender pay gap in recent years. Worse, if pay is adjusted too much lower for female workers, then it may dissuade them from returning at all. And, while the same could be said for men, males tend to be far more likely to be employed in high-paying innovation industries, thereby mitigating the risk that men will choose not to return.

The addition of female workers over the past 60 to 70 years has also helped to stabilize the broader economy as more men dropped out of the labor force. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) can be conceptualized in a variety of ways. One way to estimate GDP growth is to calculate the sum of labor force growth and productivity growth. Through this lens, we can see that a contracting labor force is a significant drag on GDP growth. Given that men have consistently left the workforce since the late 1940s, future growth will hinge on women workers continuing to take their place. Otherwise, the U.S. economy—and San Diego’s—will have to rely exclusively on productivity gains to drive overall growth, an especially risky gamble since productivity growth has slowed immensely in recent decades.

Granted, the estimates provided above are based on national figures. But, even if the dynamics have played out somewhat differently here than across the rest of the country, we need to ensure steady engagement of our women workers. It is not an exaggeration to say that our regional economy depends on it.